The Heart to Artemis Read online

Page 18

“What is your aim at Queenwood?” I asked Miss Chudleigh audaciously as we were plodding across the Downs on the walk that she took alone with every girl from the top form who was about to leave.

“To turn out the greatest number of girls conforming to an average pattern,” my Headmistress replied as precisely as if she were annihilating some troublesome fly.

“But then you will lose the few above and the much greater number below,” I protested but Miss Chudleigh shook her head.

“The individual is less important than the group.”

Her arguments left me cold. Every person alive had the right to personal development and besides, was standardization, to use the classic English expression, “fair”? Authority just twisted facts to suit its own ends. Tradition, I proclaimed, was just another word for laziness. We ought to examine every action, I thought, instead of looking at the ball that I was supposed to hit (was I not the young scholar literally sacrificed to the Games?) and discard what was merely a convention. Give me a class to teach and I would show “them” results. Meantime let us forget that awkward incident of zero at arithmetic. I had no trouble in remembering the dates of historical events.

What happened to us all? There were about eighty pupils at Queenwood during the two years that I was there. As I have written earlier, Martita became an actress, half a dozen of us wrote books, Dorothy Pilley climbed in the Alps and in the East, Doris created new daffodils. Some ran schools, others worked both with radio and films, they farmed, they nursed, they settled all over the Dominions. The moment that a new type of work opened for women, one of us was usually there. Nearly all my companions married and had families. Miss Chudleigh and Miss Johns both died during the thirties and I never saw them again after 1918 but I am still in touch with several of “the ladies of the staff.” In general, they also married or went on to other schools and escaped the “eternity of terms” that I had projected for them in my novel. The school itself ceased to exist but there is still an active Old Girls’ association that meets twice a year.

There are certain psychological factors that make a type of life less bearable for some than others. Fortunately I arrived at Queenwood with my character already formed and by some miracle much of it survived. Yet the children who came when they were nine and left when they were seventeen, how could they keep even hope? I used to blame Miss Chudleigh for her mistakes. Now that I am the historian that nobody wanted me to be, I understand that it was the age and not my poor headmistress who was at fault.

Perhaps each epoch has a particular mold that all its citizens must share. What was school but a foretaste of those army camps where millions in subsequent years faced their training also in circumstances where justice and mercy were largely unknown? One thing was spared me. What my comrades thought about my attitude was entirely indifferent to me. I demanded judgment from my peers. I could see no escape except through knowledge but I felt instinctively that this had to come through life and not from books. I intended to question the validity of every thought, to fight for my freedom and, if I could not get it, die.

There had to be a bridge between the isolation of my childhood and the everyday world. The friendships that I made at school have lasted all my life. I can concede at present that the gain was greater than the loss. Yet there was less than a knife’s edge between psychological disaster and survival, my story might easily have had another ending and though as age has chilled the emotions I can accept Queenwood as a necessary part of my experience, the impact was a shattering one and it was hell while it lasted.

TEN

To leave Queenwood was not to regain Paradise. I had supposed that I had only to leave school to be happy again but I sweated out the next seven years in complete frustration. They were the first endurance test of The Book of the Dead. How could I have known then that though experiences sometimes repeat themselves, it is always with a difference and never in their bright, primal colors? The war was responsible in part; until it ended the pressure to conform increased but there was also a change in myself. I cannot remember ever having felt lonely in childhood or even knowing what the word meant. Now I wanted passionately to be able to talk to my own generation.

The modern world does not understand how narrow existence was for the Edwardian woman. It was not a question of class, or even money, this should be emphasized, but of public opinion. From slum to palace almost everything outside the home was forbidden ground. It was only after analysis, many years later, that I realized how much of this was due to sexual taboos that were all the harsher for never being explained or mentioned in conversation. I was not allowed to go to public lectures or to accept invitations to lunch in restaurants. (This taboo did not apply in France.) I was reproved, aged twenty, for writing a business letter to a publisher to inquire about the fate of a manuscript. “What do they expect us to do?” I used to ask Dorothy Pilley, the freest among us, when yet another harmless pleasure was put out of bounds. Her only answer was to shrug her shoulders. If my Queenwood friends came to see me, we sat sedately on chairs hoping that our almost-floor-length dresses were not getting crumpled, this meant a scolding, “Can’t you girls ever learn to sit still,” and that the hairpins holding up our heavy plaits were conformably in place. Our generation, as always, was supposed to be unbelievably wicked. My mother’s friends alluded to scandals in oblique terms after glancing in our direction. They could have discussed them in the plainest words, we should not have understood them. We were much too frightened of our parents to worry in the modern fashion about how they might behave. Our rebellions took place in our thoughts, it was only after 1920 that they passed into deeds. I was a dutiful daughter (strange though this may seem) and renounced almost to the memory all that made life endurable only to hear after every fresh submission, “Why can’t you be more like other girls?” These wanted less than I did, they were not vowed to Artemis; besides how was it possible to change a cheerful and obstinate hippopotamus (my totem animal) into a graceful Edwardian miss?

In one respect I was fortunate. Nobody had less sense of caste than my family. My mother was, as my father often ruefully remarked, “an anarchist at heart.” He was blamed for promoting the office boy who had shown initiative instead of the gentleman’s son who was a university graduate. I often heard him say that if he had been to a public school he would not have been flexible enough to create his business. I should have been smacked, whatever my age, if I had dared to suggest that I was any better than my neighbors. We came from the stolid, Protestant middle class and we stuck to its training. Some of the rules I understood and still accept; if I happened by chance to have more funds or intelligence than the people around me it was so that I might help them. I must never “show off.” (I wonder if a little “showing off” is not good for the extreme young?) The conventions that I fought were either conformity of dress (I was supposed to put on a hat and gloves if I went in the country to the post box at the corner) or all that kept me from adventure or that interfered with the freedom of the mind. Mercifully, within rigorous bounds and hours, I was allowed to go out alone although this was considered shocking by many of my mother’s friends. Sometimes when she sent me to a neighbor with a message, I had the humiliation of waiting while they telephoned to inquire if it were really true that I was permitted to take walks unescorted.

Pioneers are usually Puritans, they have to be, but neither common sense nor the exemplary Jives most women led helped them in the least. We were literally freed by the war. So many families then lost all that they had, so many daughters were forced to go to work through sheer economic necessity that some though not all of the restrictions collapsed. Alas, in an age of prosperity, they recur.

The logical action if I could not advance was to retreat. Consciously I wanted to grow up but unconsciously I was drawn back to an earlier happiness and suggested to my family that if we ever went East again I could be valuable as their interpreter. They showed little enthusiasm but I had discovered that there were Arabic cl

asses at London University (it must have been through Miss Johns) and they consented reluctantly to my attending a course. The group was so small that the professor preferred to take it at his own house and I suspect that this was the deciding factor; it meant that there was no chance of my mingling with other students and “getting ideas.”

Professor Arnold fulfilled the popular conception of a scholar. He was dignified, incredibly erudite, absent-minded and even shyer than myself. He faced his three pupils helplessly in his library; I seem to remember this as a sunken room somewhere near the Natural History Museum. It was hung with dark but glowing carpets and packed with books from floor to ceiling.

We were all three there for practical reasons. There was, first of all, a nervous youth whose name I never knew who had been ordered to take an examination in Arabic before his leave expired. He had been working at a consulate somewhere in Africa and already spoke Swahili. His interest was law. I remembered perhaps a hundred words and had never learned my letters properly but I wanted to read the battle poems, the Seven Odes, in the original. I imagined myself quoting them from the top of a racing camel somewhere in the desert. Our leader was the Egyptologist, Margaret Murray. She spent the winters excavating beside the Nile; in those days we were too polite to speak of going on “a dig.” She herself was like some hieroglyphic bird as she turned her head restlessly from one side to the other, missing nothing, always wary and full of common sense, “I can’t talk donkey boy Arabic to the sheikhs,” she explained and added when I said wistfully that I wished that I could join her, “Wear a scrap of veil or even a bit of mosquito netting the next time that you are in Egypt. It can be as transparent as you like but the Arabs will talk to you more freely once they see that you respect their customs.” How many political difficulties might have been avoided if Western officials had taken her advice?

The University syllabus had prescribed a course in classical Arabic founded upon the Koran. It was the equivalent of giving an Elizabethan Bible in the spelling of that age to some cheerful French family visiting England for the first time and confirmed my opinion that universities were stupid places where people went on being children for the rest of their lives. We sat with our books in front of us and understood perhaps one word in ten; the “set book” was the Islamic version of Joseph and his brethren. Professor Arnold seemingly spoke every language of the Near East and to help us Miss Murray gaily persuaded him to tell us stories. Grammar was his love; from the root of an Arabic word he swooped off to Sanskrit or hovered longingly above Persian. The character of a race, he explained, was visible in its language, the soft Syrian vowels became a grunt of consonants in the harsh Moroccan sands. He could be kept discoursing on a single verb all the morning or, if luck were with us, turn into a storyteller straight out of the bazaars.

Sometimes he would remember that we were, after all, his pupils. “Try to say gh-rr-r,” he encouraged us, “begin in the throat and throw the sound to the back of the nose.” We hesitated, it is extremely difficult for three people to gh-rr-r in unison, then we ghrowled. “Oh, no,” I can still see Professor Arnold shaking his scholar’s head, “perhaps if you went to the Zoo it would be helpful. It is really a camel sound.”

The youth scribbled something in his notebook. Was he writing down “Practice five minutes daily at the dromedary enclosure,” I wondered, with “mouth open” underlined?

“How do you get the camels to cough?” Miss Murray was always practical.

“I leave the details of their studies entirely to my students.” The professor permitted himself the suggestion of a smile.

We never managed to gh-rr-r very well but we covered pages with exercises. It was old-fashioned and comfortable, there was none of the modern drilling in a few basic sentences, we were supposed to run, driven by our enthusiasm, long before we could crawl. I enjoyed myself but the shock of Queenwood was exacting its toll. I had lost my habitual concentration and had never learned so badly nor dreamed so much. I copied signs and thought of saddle straps as I drew the curves but my mind was not awake, I was stiff and frightened and the others thought me stupid and bored. Even my enthusiasm began to slip away when my confusion increased in spite of all my hard work. Occasionally there were other complications.

“She lifted the pomegranate,” I was very glad that I had actually seen the fruit, the consul-to-be noted its equivalent in Swahili, the professor bent over his Koran. “Beholding Joseph’s beauty, the knife slipped...” he looked up in agitation, “Miss Murray, Miss Murray, this is very different from the Jewish version, do you think we ought to omit the next six lines?”

Miss Murray caught my eye and grinned. Joseph, although he ultimately resisted temptation, gave a precise description of his physical reaction to love that was highly distressing to British reserve. We started again, Miss Murray began to laugh, we leapt a whole page and eventually reached harbor in some pious sentences about the wisdom of virtue. The difficulty was that words such as “zealous” and “abnegation” were hardly the terms that a traveler needed to order a glass of tea or find his way out of a souk.

After a second such experience the professor shut his book gratefully and turned to his colleague, “I suppose you have heard about our new Persian course?”

“I have seen the prospectus, yes, but I have three classes of my own...” Miss Murray looked up with the defensive air that I saw then for the first time when lecturers suspect that they may be asked to take extra work.

“The authorities decided, I think unwisely, upon a formal inauguration. There was first the benefactor who had provided some funds on account of his interest in Omar Khayyam, then the Persian Ambassador decided to come with several gentlemen from the Foreign Office to support him and there was an unusual number of our colleagues. They all arrived at the classroom punctually at three.”

“In top hats?” Miss Murray was irrepressible.

“I presume they came in appropriate dress. It seems that there was a single student. A lad going out to an oil company, I believe, near Tabriz. The Ambassador addressed him from the platform upon the beauties of Persian poetry and a diplomat spoke most feelingly afterwards about the influence of Eastern philosophical thought upon Western belief. Unfortunately we had a letter from the young man this morning, saying that he proposes to continue his studies elsewhere. It was his first lesson and I am afraid that he was rather shy.”

My next adventure was Sakuntala. An Indian student rang our doorbell one evening and, to my mother’s amazement, asked for me. Where had I met him, she inquired? Nowhere, I protested, she had seen my fellow pupils when she had taken me to the first class and she had known my exact whereabouts during every moment of the last month. No, I did not think that it was the brother of the Indian girls at Queenwood. They had been younger, in the Lower School, and I had seldom had an opportunity of speaking to them. I had never been asked where I lived but if the man were a foreigner and in distress, according to the Bedouin traditions of hospitality we ought to see him and offer him help.

My family seemed doubtful that this was the correct procedure. Duly chaperoned however by my mother and a friend who happened to be staying with her, we entered the library where he had been asked to wait.

It was “much ado about nothing.” A terrified Hindu student with a letter from the University in his hand had called to ask if I would take tickets for a private performance of Sakuntala in an English translation arranged by some dramatic society. He had got my name from a list of those taking Oriental languages. It was a Sanskrit classic and had little to do with Arabic but perhaps, he ventured, I might be interested.

I had never been to India and its literature seemed remote to me but I took two tickets, I think that they were four and sixpence each, he bowed and left. The meeting had lasted precisely three minutes. Then the storm broke. Girls never went to amateur performances given by students. I should understand when I was older, (I was then nineteen!) Besides, who knew what was in the play?

“It is a religi

ous drama,” I remarked icily because I knew that this was a matter of principle and that it was essential for me to insist upon my right to see it. Why must I be forbidden every activity that took place outside the home? Eventually we reached the usual British compromise. I might see the play provided that I could persuade Miss Johns to come up from Queenwood, it was during the holidays, and accompany me to the theater.

The performance was a hilarious occasion. Sakuntala had been translated about 1860 by an English gentleman with a fondness for the word “sublime.” The scenery had been borrowed and was not remotely like a jungle while most of the cast was English with an obvious terror of declaiming poetry out loud. The play also went on for five hours. I tried to be worthy of the occasion until the Queen flung herself onto the stage in all the glory of a dozen shimmering veils and a pair of sturdy, black walking shoes as she was being abandoned to the sublime ferocity of the more than sublime tigers. I reverted to childhood and howled. “Try to control yourself, Winifred,” Miss Johns whispered, tears pouring down her own cheeks. The newspapers described it the next day as a very moving performance.

“Ah, what I expected,” Professor Arnold remarked soberly when I answered his polite inquiry at our next lesson. “I think perhaps I was wise to immerse myself in my work.”

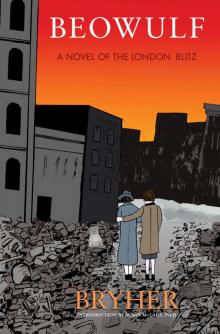

Beowulf

Beowulf The Heart to Artemis

The Heart to Artemis