The Heart to Artemis Read online

Page 19

One victory led to another. After such an innocuous experiment I was able to persuade my parents to let me join Miss Murray’s own class in elementary hieroglyphics. It was actually given inside one of the University buildings and I had to endure a number of family lectures upon not allowing myself to be “influenced by people.” None of my twenty fellow students ever spoke to me nor I to them. I do not think they talked among themselves. It seems crazy today but it was part of the fabric of that so-called “golden age”!

I did not find the hieroglyphics as difficult as Arabic. I remembered the pictures at once. It was easier being taught than learning them alone because I could ask questions if I did not understand them. I did not realize it at the time but drawing the signs probably allowed some of the feeling for art that I had so sternly repressed to emerge into consciousness. Sometimes a new symbol could illuminate a day.

At the end of the first term I was offered what might have been a chance of escape. We had been sent to a strange classroom and Miss Murray herself had offered to show me the way back to the entrance. “Why not ask your parents to let you come all day and train properly as an archaeologist?” she suggested, “We need assistants badly and you would like the work.” It was the last time for six whole years that any adult offered me help.

My family said no. I was too young. I must certainly stop at home if classes put such foolish ideas into my head. I might get stranded in some unheard-of place, lose my ticket, have things happen to me that they could not possibly explain. I fought back. I should be old enough because the training took three years, there would be a group of us in Egypt (I thought it wiser not to mention that we should probably sleep in tents), why was it right to be with all those girls in Queenwood and wrong to be with students interested in what I liked? They said no again but not quite so emphatically and I think I might have persuaded them at least to let me begin if an English family that my father knew had not invited me to spend the next spring at their place in Lebanon and they even offered to lend me an Arab horse. My father this time gave his consent but war broke out before I could leave.

Perhaps I had a narrow escape. A little easing of the intolerably frustrated state in which I lived and I might have become the conventional scholar so absorbed by research that I should never have had the adventures for which I was born. I began gradually from this time to divest myself of the Arab world, it was a dream’s misunderstanding, as I came to analyze its attitude towards women. Of course I thought of it occasionally but in general it was a scrap of papyrus from the past upon which no complete text was ever written. My true destiny was the West.

What a disappointment I was to my parents! All their friends had liked me as a child but here I was with the raw aggressiveness of a boy, clamoring to be loosed upon a world that had no use for me. My father might have coped with the situation if I had had a mathematical mind but what was he to do with a young savage who was only interested in tearing society apart to see how it worked? It must have been disconcerting when a guest, meaning to be kind, asked me what my hobbies were and got the answer, “I want to find out how people think.” Once in an unguarded moment I said something about writing. There was a roar of laughter and a visitor answered, “Oh, no, Miss Winifred, I’m afraid that is a little out of your range but I’m sure you’ll run the garden splendidly in a year or two.” Usually I was careful and silent. I prayed to be forty, knowing that as long as I was young nobody would listen to me. I seldom had more than half an hour a day to myself. It taught me concentration because such moments were so precious no noises could disturb them and I usually spent the time memorizing pages of poetry to repeat during our interminable walks. It was a training in the ancient oral tradition but also a dangerous practice because it absorbed the energy that should have gone into creative work. Yet what else could I have done? It was morbid to read so much, they said, and selfish to want to write.

I do not know how I should have lived if it had not been for one of those little magazines that, as Gertrude Stein was fond of quoting, “have died to make verse free.” It was Poetry and Drama, edited by Harold Monro. The English contributions were too conventional to touch me but F. S. Flint had written articles on modern French poetry and I found in them for the first time the magic word “Mallarmé.”

Mallarmé’s ideas exploded in my head. We desire perfection when we are young, not knowing that inspiration is the skin boat of the seal woman, here momentarily, as suddenly vanished. I had been groping towards the idea of a poésie pure and I was willing to give up everything else to find it. I was utterly alone and for that reason, le verbe, as the French would say, had become of supreme importance. I thought of it as Pegasus and saw it as a way to freedom. In my innocence, I took the words literally and supposed that l’azur meant that Mallarmé had wanted to be a cabin boy and run away to sea. Unconsciously, I imagine, I caught some echo of his own unhappy schooldays although I knew nothing then about his life. Perhaps I was not so wrong after all, remember the famous yole? I had so great a thirst for life that when it came to me through certain of the lines, I could hardly bear to listen to them. There was a sense of infinite adventure in the words, what were they but a huge Atlantic roller, curling over and bursting into foam? It was as if a captain had suddenly come up to me and said, “So you want to go to sea? Very well, go forward, we’ll have to try you out.”

Purity of apprehension by no means implies an ability to handle form. About this time my father paid for some of my incredibly bad verses to be printed. In retrospect, I do not think that this practice is necessarily wrong, all apprentices have to learn their trade and we cannot expect to waste paper at a publisher’s expense. It is also less vanity than a desire to be accepted as an aspirant by one’s fellow writers. I had never spoken to an author, praise then would have seemed patronizing, rather like a Queenwood mistress deigning to approve an essay, but if I were to develop I had to leave home and success might soften parental opposition. I was nineteen, it was my first book and I had hazarded, if you will, all I knew upon a throw of the dice.

A few days before the verses were published I discovered Mallarmé. I knew then that everything that I had written, under conditions of the greatest difficulty, was meaningless and that it was doubtful that I could ever produce a sentence that I might have carried to the Rue de Rome. It was a profound shock because it literally destroyed all the hope that I had in life. I tore up my manuscripts and apart from an almost factual account of my schooldays, I wrote little more for twenty years (Mallarmé seems to have that effect upon people) yet during that time my principles of conduct were founded upon his ideas. He had felt intuitively some of the steps taken later by Freud to liberate the mind from purely conscious thought. It is a measure of his stature, not only as a poet but as a leader.

Young fibers are resilient. Prowling around a bookshop, I discovered a slim, green volume, Des Imagistes, and flung myself upon its contents with the lusty, roaring appetite of an Elizabethan boy. I was discontented with traditional forms but this was new, it said what I was unable to write for myself.

The horror that the Imagist manifesto produced had to be lived through to be believed. Poetry had reached an incredibly low level in 1913 although it was fashionable to quote it continually in conversation. Verse then was distinguished from prose because each line began with a capital letter and it rhymed. It was improper to mention the modern world except in terms of horror; the writer should be down on his knees in the clover (odorous was a better word than scented) waiting to be stung by a bee. It was also important to use poetic language, we “quothed” rather than spoke. Naturally “free verse” was confused with “free love” and not to rhyme was felt to be a form of cheating.

I think that the cause of such opposition came from first lessons fixing a definite pattern in a child’s head. It is natural to begin with ballads and these are usually written in some easily remembered form but they are a beginning, not an end. Our opponents forgot that alliterative poetry was the

basis of English literature and that the ability to hear and use the slight pause or silence between parts of a line or the portions of a sentence is one of the writer’s important tasks. We do not need to match love with shove but to vary this break so that it is never monotonous but always perceptible to the trained ear.

I have full respect for the popular arts but the function of the artist is vision. He must be in advance of his time and as to know is to be outcast from the world, why should he expect recognition? Fame is merely the badge of long service. His duty is to his art and that implies detachment; he is the twin of the designer of supersonic aircraft, his ivory tower is his drawing board, it is not his function to produce the commercial air liner or the family car. I have a profound contempt for the writer who speaks of making his work intelligible to the masses, he is not serving them but betraying their trust. Our job is to feel the movement of time as its direction is about to change and there can be no reward but the vision itself. It is natural that we should be both disliked and ignored.

Our youth makes us whether we like it or not. The rest is simply sharpening and experience. I felt the approach of another age and the Imagist poetry made me drunk with joy. Some of the writers were American; they also wrote of the Mediterranean that had been a part of my childhood and they used new rhythms and exciting sounds. There was a feeling of revolt in the air, nobody had spoken to me about it and to this day I do not know precisely why I leapt into the twentieth century without a single, backward glance. Perhaps we cannot escape from our generation, no matter how much we may be isolated from it, it is a universal movement and we have to drift with it or perish.

I risk giving the impression that I was living in the bourgeois environment that Flaubert described so well. This was not the case. Our house was full of pictures. They were traditional and friends said indignantly that they would not enter a man’s home if he hung futurist daubs on his walls but there were frequent visits to galleries and museums. I was able to listen at the highest level to discussions on law and the political trends of the time. The cause of the rift between myself and my surroundings was purely sociological. In 1913, women belonged in the home. My family were truly frightened of the free-thinking little monster that had emerged in their midst and naturally did their best to discourage my “morbid ideas.” It would have been the same wherever I had been born, in a cottage or a mansion, in Kent or France. Slavery may be a gentle thing but the threat of the rod is always in the master’s hand. It was not until the war gave women the possibility of economic freedom that circumstances changed. I could not possibly have understood this at the time. I wanted to sail around the Horn or, if this could not be managed, go as near it in adventure as possible and then write about my voyages in an entirely new form. Nothing else mattered to me. No wonder I scribbled in my notebook, “I waste in a raw world, dumb, unendurable and old.”

Under such circumstances, the young usually fall in love. I followed the pattern but with a country, not a person. America was my first love affair and I have never gotten over it. My mistress perhaps, because we have both been perceptive and also inconstant. I am deeply and traditionally English by temperament but whatever recognition I eventually received came from the other side of the Atlantic. Sometimes I think that Fate allowed me to have my desert training as a child for a special purpose. It enabled me to see both sides of two powerful civilizations that might understand each other better if they did not speak the same language. We are nearer our Atlantic cousins than we shall ever be to Europe but words change profoundly in meaning when there is an ocean between them. “I want to go to America,” I said, to everyone’s astonishment because until then I had always talked about the East. “You’ll soon get over that enthusiasm,” they laughed but I shook my head. I knew better, miracles happened in America. Girls had jobs.

I have spent a lot of my life trying in small ways to bring Americans and English together. If anything that I have done has been worthwhile, it was due originally to an economic fact and to Imagist poetry. Perhaps, as in the Middle Ages, a proper secondary function for the poet is to be an ambassador. H. D. had written:

Hermes, Hermes,

The great sea foamed,

gnashed its teeth about me;

but you have waited,

where sea-grass tangles with

shore-grass.

I, too, waited for another five years.

I never asked to return to my drawing classes nor have I ever willingly had pictures in my room. I tried to detach myself from possessions, this was reasonably easy apart from books, and as whatever I enjoyed was usually forbidden, I never showed more emotion than I could help. I suspect, however, that my father had wanted to be a painter when young. I still have some of his sketchbooks, they are mostly full of Indian landscapes, and his greatest friend had been Val Prinsep, one of the Pre-Raphaelite group. He would not collect old masters, “Always buy a painting by a living man, Miggy, what use is money to him when he is dead?” but his taste was naturally traditional, he never made the leap to modern art. Prinsep had died when I was ten and I had never met him but my father was the guardian of his eldest son, Thoby, who often came to our house. Val Prinsep had given my father one of his pictures. It dropped from the wall for no apparent reason the night of my father’s death.

It must have been through this early association that we knew Sir Luke Fildes. We often used to have tea on the lawn of his house in Melbury Road that was so quiet that we might have been in a country village. For some reason or other, I had to sit to him for a portrait. I resented this at first but Sir Luke’s quiet kindness soon smoothed out the prickles. He belonged to another age and though he lectured me gently upon the need to give up everything for art, his own life seemed as constricted as my own. The flatness and fidelity of nineteenth-century paintings embarrass our modern eyes. We should not impute a lack of integrity to Victorian painters because we have learned to look at light and color in another way. It is not enough to give a life’s devotion to the Muses. They choose, they touch one person with a feather and leave the rest and often, to our surprise, it is the one who seems to deserve it least. Many factors besides vision and skill go to make a masterpiece and perhaps the man who is a bridge between two generations has the best chance of survival. Sir Luke had fought a hard battle to be allowed to paint at all in a period of ugliness and horror. I have never met anyone who approached art with more humbleness.

“You keep as still as a model,” he would sometimes say approvingly as he cleaned my portrait face with a sliced raw potato. The birds sang outside in the garden and although he was usually silent, he lifted the veil one day from a corner of the Victorian world that was so deeply cruel underneath its placid surface. “I knew a boy,” he said, wiping his brush on a piece of rag, “he wanted to write instead of going into the family firm and made things worse by marrying a girl from a different group than his own.” It sounded like the Little Meg’s Children that I had read in the nursery but I listened. “His people used their influence to stop him from getting work and his wife and the baby died from what they called pneumonia but it was really starvation.” I nodded, I had always suspected that there were more happy endings in books than in life. “They crushed him into submission,” he began to paint again with slow, careful strokes, “help everyone you can but it isn’t always possible.” By pure chance I was able to check the story shortly afterwards and every word of it was true. It is foolish to imagine that there was more security then than there is today. Horace Gregory, who has so profound a knowledge of the Victorians, told me years afterwards that its underworld was perhaps the most vicious of any in English history.

Sir Luke seemed like a grandfather and I was a restless modern who welcomed the machine age that he found destructive. Yet he set me an example of patience and when I think of him now, standing beside his easel under the high windows, I am ashamed that I often responded so roughly to his advice.

At least I got plenty of exercise. I went out with

my mother in the morning, with a French lady for conversation in the afternoon, I wish she had done more to correct my accent while we wandered up and down the Serpentine among the waddling, peppermint-colored ducks, and after my father got back from the office in the evening we went for a stroll before dinner. Godliness was certainly inherent in the miles that I covered during the day. I was used to being in the open air but I longed to have time for my own work and friends with whom I could talk, all night if need be, about voyages and books. I am most grateful to my father for one thing. My cousin Jack, who was about my age and stayed with us frequently, taught me to type and then my father gave me a machine. It became at once an extension of myself. (It is recorded of me that I once snatched it from the hands of a page boy at a hotel, saying, “You can’t carry that, it’s my soul.”) I suppose it was because it gave me the illusion of print but I soon became incapable of writing anything by hand. Even now, if I have to take notes in a library, I usually trust to memory, I cannot read anything that I have scribbled.

I do not mind the changes in modern London so much as the different colors. Neon lighting has standardized the sky. It is the red of metals whether we are in Knightsbridge or Fifth Avenue. In 1913 the horizon was a deep blue and the sunset between the lamps at the end of a distant street had the effect of a country orchard. Even the solitary car moving slowly across a square was more like a phosphorescent fish in the dusk than a means of transportation. We thought that the city was terribly crowded, people asked each other how humanity could stand the pace, they still grumbled that taxis had replaced the hansom cabs while I wondered how I could endure the dragging days that, if I had been allowed, I could have filled with life.

I was always repeating poetry to myself during these walks and there are certain lines that, if I see them now, bring back those Edwardian days as if they were happening round me. Hodgson’s “Bull” is one of them and three lines of Vildrac that I had found through Flint,

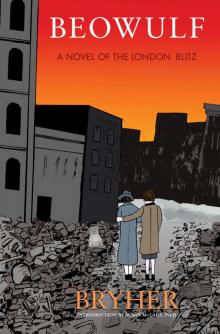

Beowulf

Beowulf The Heart to Artemis

The Heart to Artemis