Beowulf Read online

to

SYLVIA BEACH

and the memory of

ADRIENNE MONNIER

Copyright © 1956, 1984 by W. Bryher

First Reprinted Edition, © 2020 by Estate of W. Bryher

c/o Schaffner Press, Inc.

Introduction: “Comrade Bulldog Among the Ruins”

Copyright © 2019 by Susan McCabe, Ph.D., all rights reserved

No part of this book may be excerpted or reprinted without the express written consent of the Publisher.

Contact: Permissions Dept., Schaffner Press, POB 41567

Tucson, AZ 85717

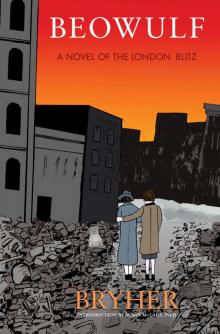

Cover, Interior Design, and Illustrations by Evan Johnston

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Information, Contact the Publisher

Printed in the United States

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-943156-90-0

E-Book ISBN: 978-1-943-156-91-7

INTRODUCTION

“COMRADE BULLDOG AMONG THE RUINS”

“Two wars in a single generation asked too much of any race.”

–Beowulf

WHO OR WHAT IS “Beowulf,” the title of a book chronicling the Blitz? Moreover, who is this writer? Primarily an historical novelist, Bryher (1894–1983), little known today, her writings largely out of print,1 was a pioneer, a model of personal and cultural defiance. Before World War II, she published among other works, two volumes of poetry, two early coming-of-age memoirs, Development (1920) and Two Selves (1923)—both early accounts of gender dysphoria in modern literary history. Bryher was a woman, but felt like a boy, as she claimed, from infancy.

“Comrade Bulldog” was Bryher’s working title for her first novel that she later renamed Beowulf, taking the same title of the Anglo-Saxon foundational poem from the early 10th century, recorded by an anonymous scribe, long before England existed and half a millennium before the Empire was born. Beowulf, the armored hero of the ancient epic, travels from Geatland—what is now Sweden—to assist the Danes in combating the monster Grendel, and Grendel’s mother. While successful in fending them off, his old age (fifty!) presents another challenge, a dragon, terrorizing his subjects; he slays it, though mortally wounded as a result.

In this hybrid docu-novel, Bryher has morphed Beowulf into a bulldog, a miniaturized plaster statuette, a popular mascot to decorate a teashop. Known as “The Warming Pan,” this establishment became the pivotal locale of her novel, based on an actual tearoom run by a pair of women. As Bryher describes: “Selina and Angelina supplied their clients with soup, meat, two veg and dessert for two shillings and ninepence. They were country people, they bought all the ingredients they could from farms and the cooking was plain but excellent. Such places are now extinct. I liked it because, as I said, I could go there without fear. There was a large notice, Dogs Welcome, hanging on the door and as I am to those, but only those, who know me intimately, Fido, I felt at ease and knew that I should not be hustled out.”2

Using the fusty classic’s title was her joke with legend; her bulldog is humanity’s finest. By the end of the novel, it seems we are all plaster—when those staying near the City faced total annihilation (one rumor had it that London could be demolished in three years). Bryher probably foresaw that, although Britain was wholly unprepared for World War II, its bulldog spirit would triumph in the end. However, as in legend, the first battle waged and won, like the Great War, the second amounted to a muted victory, in which the victor prevails, though mortally wounded. We are not supermen or superwomen, Bryher seems to be telling us, nor could she idealize England’s own eroding Empire that had sustained the Victorian-era sense of solid well-being.

Beowulf was actually the first of Bryher’s eight novels, that received critical acclaim in the 1950s and 1960’s. Instead of attending to the heroic, she focused upon the lives of ordinary citizens as shaped or disfigured by their rulers. She put it starkly: “there would be a gulf between the bombed and the unraided.”

Bryher was allergic to nationalism of any stripe—an obsession ignited when she was five, when, visiting the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris, she recognized that the Boer war made the French disdain the English; at first she wanted to put up fisticuffs, but was disarmed when she learned the French shared her values of égalité, fraternité, liberté.3 These words entranced Bryher—ultimately leading to Beowulf. But to understand her engagement with history, and her first book that confronts the daily reality of London during World War II, the reader needs some familiarity with Bryher’s own history—and her most significant and enduring love relationship with the imagist poet H.D.

Bryher was born Annie Winifred Ellerman, on September 2, 1894 to the then-unwed couple, John Ellerman and Hannah Glover. Her father had made a fortune in shipping and other enterprises, and upon his death in 1933 was said to have been the richest man in England. The constraints of the Victorian age made her wonder “if adventure had died just before I was born,” which propelled her to conclude that “if I wanted to be happy when I grew up I had to become a cabin boy and run away from the inexplicable taboos of Victorian life.”4 At an early age, she secretly sensed what Havelock Ellis, the sexologist, later confirmed in 1919 that she was “a girl only by accident.”5

During her early years, Bryher travelled extensively with her parents, spending winters in Italy, Egypt, Greece, and the south of France, and summers in Switzerland. The family spent little time in Britain. Travel advanced Ellerman’s shipping business, and fulfilled his desire to escape snobbery and restraint. During these early treks, Bryher learned Arabic, tried to decipher hieroglyphics, rode her first camel, learned to barter, and traded thoughts with Sufis. At twelve, she had a vision near the wall of Euryelus, the ancient fortress at Syracuse, where, according to mythic lore, one’s fate is sealed: “seized by the throat, barely able to breathe,” she was hit with “a terrifying sense of ecstasy,” and understood with undeniable certainty that Clio, muse of history, was destined to be her life’s mistress: to “write of things was to become part of them. It was to see before the beginning and after the end. I almost screamed against the pain of the moment that from its very intensity could not last.”6 Close study of the past helped her to view history as non-linear and see beyond it and the present, as captured in this assertion in Beowulf: “the distant thuddings of the mobile guns were the footsteps of mammoths.”

In 1909, when Bryher was 15, her mother gave birth to a boy, John Jr. Her father, knighted for his help in the Boer War, purchased a mansion in Mayfair, 1 South Audley Street, close to Hyde Park and adjacent to the Dorchester Hotel. Under English law, their newborn was also destined to be illegitimate; thus Bryher’s parents snuck off to obtain a “Scotch Marriage.” Bryher’s childhood utopia came to an abrupt close with her brother’s birth. Her parents shifted their fantasies to John Jr.’s future, throwing the teenage Bryher into paroxysms, not only of anger, but despair. Increasingly, Bryher disappointed her mother’s expectations that she would develop into a “lady.” (She puts it for one of her Beowulf characters: “everything should have been so different if she had been a man.”) As a child, it was easier to maintain the fantasy of boyhood. One of the family’s guests criticized Bryher as not “quite normal,” advising they put her in school “to knock the edges off.”7 Much to her horror, they followed this suggestion, enrolling her at Queenswood Boarding School, twenty miles outside London, as a day-student.

During this period, she began calling herself Bryher after the wildest island in The Scillies, off the coast of Cornwall. Fiercely independent, she wanted to make her way without the assistance of her father’s surname. After Queenswood, Bryher returned to Audley Street, and spent the First World War studying in her father’s library, attempting to write, and meet poets. She corresponded with the American poet, Amy Lowell, who was friends with a nu

mber of Imagist poets, including H.D., born Hilda Doolitttle in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania on September 10, 1886. Hilda had followed her one-time suitor, Ezra Pound, to Europe. Through Pound, H.D. met and married Richard Aldington. Through Lowell, Bryher discovered H.D., deeply moved by her debut collection, Sea Garden (1916).

The couple’s forty-two-year, intimate, tumultuous yet productive relationship began as World War I ended, and would continue on to H.D.’s death in 1961. At the time of their meeting, Aldington, H.D.’s soldier husband, was embroiled in a blatant adulterous affair, leading her to escape to Cornwall at the invitation of the Scottish music critic and composer Cecil Gray. With her photographic memory, Bryher memorized all of H.D.’s poems, and descended upon her there on July 17, 1918. H.D. was fascinated with this amorphously-gendered being. The H.D. and Bryher saga felt destined by both women. While sometimes maintaining separate households, they remained discretely together, corresponding when apart nearly daily. H.D. wrote “Remember that it all began with a bluuue swalllllow and you—”8 As a result of her tryst with Cecil Gray, H.D. was now pregnant with Perdita (“Pup”), and meeting Bryher felt like rebirth. Now separated from Richard Aldington, H.D. committed perjury and registered Perdita as his, only to fear he would unveil her and Bryher’s unusual state of affairs—two mothers and a baby.

An unusual couple, Bryher was five feet, next to the very tall H.D.; Bryher’s smallness, H.D. observed, made her like a literary Brueghel, who is said to have put his diminutive size to advantage by doing sketches under a table, invisible to those unobserved.

H.D. and Bryher explored the physical realms of Cornwall, Greece, Egypt, and aesthetic and intellectual worlds, too, in their mutual fascination with cinema and psychoanalysis. They shared visions in Corfu, cultivating a telepathic form of communication. Their birthdates separated by eight days and eight years, they celebrated the “octave” together. But they moved cautiously into the unknown realm of their relationship: one a bisexual, the other proto-transgender. Bryher’s parents, particularly her mother, kept her pinned to her shawl. The couple finessed their relationship by burying it in plain sight. Bryher asserted her freedom by marrying Robert McAlmon in 1920 on her trip to United States with H.D., H.D.’s mother, and baby Perdita.

Sir John gave McAlmon funding for Contact Press, that published some of the bright lights of modernism—among them, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Djuna Barnes, H.D., Bryher, and Mina Loy. As Bryher’s husband, McAlmon provided a cloak of marital respectability for her and H.D. One of his favorite haunts was Paris, where Bryher and H.D. were to meet Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. Bryher also met and became fast friends with Adrienne Monnier, the proprietor of the bookshop, La Maison des Amis des Livres, and her lover, Sylvia Beach, who with her help, established Shakespeare and Co., the iconic English language bookstore that was to become the nexus for poets, artists, and playwrights in Paris during that time and for decades after. Bryher’s mother sent a plaster bust of Shakespeare as mascot for the store—the “post-office” used by Bryher and McAlmon to correlate their stories of togetherness, while living distinct lives.

But McAlmon’s decadence proved too much for Bryher. She divorced him, marrying filmmaker and photographer, Kenneth Mcpherson, and adopted Perdita (aka “Pup’) in 1927. Kenneth was not only a lover of H.D., but a creative force in his own right and a good friend to both women; theirs was an unconventional family. He and Bryher built Kenwin in the Bauhaus style, in Switzerland, its name deriving from the first syllables of their names—Kenneth and Winifred. Kenneth also directed three experimental films, the most complete, Borderline (1930), featuring Paul Robeson, his wife, Eslanda, H.D. and Bryher. With an avant-garde montage, it exposed undercurrents of white supremacy.

In 1933, Bryher witnessed brown shirts and military operations in Berlin, and wrote a piece openly criticizing Britain in the shutdown of Close Up, the trio’s experimental film magazine, “What Will You Do In the War?”9 She warned of heightened militarism, displaced persons with meagre luggage. At age fourteen, Perdita marched in Hyde Park to protest Nazism, and she felt her whole youth a build-up to war.

H.D. and Bryher’s relationship was complex, involving them in numerous “psychic” triangles, including one with Freud, with whom Bryher arranged for H.D. to consult in 1933 and 1934, during the poet’s writer’s block. While H.D. was in analysis, Bryher widely distributed J’Accuse!, the pamphlet by S.M. Salomon, published by the World Alliance for Combating Anti-Semitism, that contained numerous evidentiary photographs and testimonials, gathered from reputable news agencies and eye-witnesses, exposing the barbarity against Jews: torture, beatings, interrogation, normalized through hate articles and armed militia.10 H.D. asked Bryher for some for Freud and others. H.D. told her that Freud “broke his great analytical rule of not noticing mags” in picking up J’ACCUSE; he “almost wept” that the English had done this.11 Still H.D. resisted what she saw as Bryher’s “warpath” mentality, wanting to savor her hours with the aged Freud. Impressed with Bryher, Freud called her a “northern explorer,” though asking if she was Jewish, he answered the naive question that there “was no trace.” A skeptical Bryher: “So I said rubbish I wanted to be a Jew because David was tiny but slew Goliath.”12 Freud saw her savior complex writ large. At this point, Bryher embarked on a six-year crusade of rescuing refugees from the Nazis, obtaining visas, and even buying passports on the black market.

In 1936, Bryher warned in her new publication, Life & Letters: “Every time that you laugh about not having the time nor the brains to bother about foreign affairs, you will just go and water the lupins, you are making it a little more certain that you will lose eventually, your garden, your home, and your life.”13 Bryher echoes this in the words of one of her characters in Beowulf: “How does being an ostrich save one from disaster?”

When Hitler invaded Poland, our couple was at Kenwin in Switzerland with the psychoanalysts, Melitta and Walter Schmideberg (Melitta was the daughter of the eminent child psychologist, Melanie Klein), huddling around the wireless. Two days later, Britain, France, Australia and New Zealand declared war. Bryher imagined herself during the Great War “struggling up the lane in the Isle of Wight towards the post office as if the intervening years had been wiped out with some dark sponge.”14 A soldier in World War I, Walter spoke of its first dead. H.D. wrote George Plank that “the last 20 [years] have simply dropped out, simply gone and one is just there back in ones [sic] early middle age.”15 She coaxed herself: “I must pull myself together and live or die. I don’t think I’ll do the latter.”16

With war announced, another abyss opened: Bryher’s mother, Lady Hannah Ellerman, died on September 17, 1939 in Cornwall. Bryher could not make it back in time to be by her mother’s bed-side. That same month Freud died. Relieved Lady Ellerman and Freud would be spared this new war, the couple nonetheless felt a terrible sense of loss and time disjunction. Both bi-centurians—with Bryher born in Queen Victoria’s reign, like the teashop owners in the novel, held a panoramic sense of seismic change. H.D. and Bryher were middle-aged—53 and 45, respectively, when WWII began. While H.D. strove to survive through “ancient rubrics” and “spiritual realism” in the first section of Trilogy, Walls Do Not Fall, published by Oxford in 1944 (though written almost simultaneously to Beowulf ), Bryher could only live moment to moment, feeling “war was Time in all its ponderous duration. […] People must live, but sometimes waiting in line, she wondered why.”

The so-called “phony war” lasted from approximately September 1939 until July 1940, with the Germans embroiled elsewhere on the continent. Many in the populace, such as Robert Herring, editor of Life & Letters, felt “in the dark” on many points. Advising that “[g]asmasks are practically second-nature,” along with hat and gloves, Herring prepared the returnees, not knowing Bryher would stay behind.17 The sidewalk edges were chalked white to prevent falls during a raid. Air-wardens commandeered the streets. In Beowulf, Bryher describes how people sometimes had to crawl to shelters.

>

H.D. took the last Orient Express back to London in November 1939. At 48 Lowndes Square, the flat H.D. inhabited after her Freud sessions in 1934, H.D. saw London brace for attack with the mandatory blackouts, fire watchers, stretcher vans, shelters, and mobile canteens. She perceived how gender standards had altered, conveying to Bryher that “the streets are full of attractive girls in long blue trousers, ambulance, and other oddments in short skirts and short hair […] the ambulance drivers use their blue pants, like yours and Pup’s. All very familiar and sea-shorish.”18 Both H.D. and Perdita noted the subtle but eerie switch from white bulbs to blue. London was pulling itself together.

H.D. lunched with Perdita regularly at “The Warming Pan” where she went for “escapes” to find a shadow of the familiar “old world” of London. Adversity initially fed H.D.’s magic. Seeing herself as “analyst poet,” with a small fund Bryher had set up, she reached out to help others in extremes whom she met at the tearoom, or those who, like herself, had survived World War I. H.D. wrote her friend Silvia Dobson, “I am expecting Br., end Nov or early Dec. But I am here, hale and hearty, moving about like a fire-fly. I find the black-out very beautiful and exciting, too,” remarking upon an air-warden who “found a chink of light.”19 Perdita recognized “Kat,” (H.D.’s nickname) as a species distinct from her other mother, “Fido” (Bryher’s nickname), diagnosing: “She has one of those poetic, detached natures which see the best in all, even the black-out; she finds it so beautiful, the emergency lamps are like fairy candles, girls in tin helmets like at a fancy dress party.”20 Perdita admitted she herself couldn’t stop swearing. She knew the blackout wasn’t likely to revitalize Bryher, though H.D. compared her to “a little Atlas.” Bryher confirmed to Norman Holmes Pearson (1909–1975), a professor of English poetry at Yale, who would remain close friends of both women into the future: “H.D. seems to find black outs poetical, I am sure I shall find it depressing.”21

Beowulf

Beowulf The Heart to Artemis

The Heart to Artemis