The Heart to Artemis Read online

Page 6

We spent part of every winter but one between 1901 and 1907 in Italy, going on from there twice to Egypt and once to Sicily. We missed only 1905 when we went to Spain and Algeria instead. In 1908 and 1909 we did not go so far afield but stayed in the South of France. The summers were spent in Switzerland with sandwiches of time in France and England. I counted my age by the countries that we visited, and the additions to my history books in the Stories of the Nations series.

The greatest gift parents can give their children is experience. It is far more valuable than either care or money. These years abroad deepened and shaped my whole life. They extended my perceptions because there was something new to learn daily but it came from my then level of consciousness, not out of theoretical advice or books. It is growth that is important; too much protection is as dangerous as none at all. How often at all. How often the experienced soldier survives where the recruit is killed. I am particularly grateful that my parents brought me up free from routine (that came in adolescence when I was better equipped to resist it), and that I was toughened by much exercise. How otherwise should I have got through the subsequent changes and wars?

A short time ago I stood on the Pincio looking across Rome. It was a gray, wet morning in early May. I did not pretend to know the modern city, I had never lived there, but the flutes of tiles and steps, the domes and towers, the travertine and marble were so familiar deep under consciousness that they were part of my own skin, I could not remember when I had seen them first while the difficulties of our early travels were as vivid as if they had happened yesterday. In 1902 it was not a matter of a few hours in a clean and comfortable aeroplane between London Airport and Ciampino, the journey took from two to three days.

How can I make people understand what the trip was like fifty years ago? There were no motorcars, we traveled by steamer, train or horse-drawn carriage, sometimes we rode. There were no passports, I had my first one in 1919, nobody spoke English but French was a lingua franca everywhere in Europe and, if necessary, in remote districts, we drew pictures of what we needed. The trains were dusty and unheated, occasionally porters brought round “foot warmers,” long metal cylinders filled with hot water, but my legs were too short to reach them so that I was wrapped in a rug. It was so dirty that we always kept some old and special railway clothes. There were no dining cars at first (I resented them when they arrived, it was much more fun to picnic in the compartment) and no baths nor running water taps in the hotels though enamel tubs were brought to us with cans of steaming water. All the same, I was kept clean, too scrubbed, I often thought, for comfort. There were many insects; bugs, fleas, lice and scorpions. I was drilled to pull my little pigtails forward whenever I sat down; we wore tiny muslin bags full of insect repellent sewn into our stockings and vests. (An English doctor who had been in India had told my mother of the trick and it worked.) Yet again this was an advantage in my later life, fleas never shocked me, I merely went to work with soap and powder. We take our water for granted. I learned that there was no greater crime than to drink it unboiled, if I were thirsty I had to wait patiently perhaps for a couple of hours until we could get tea or occasionally mineral water. (This was suspect because they had a habit of filling the bottles at the fountains.) We never touched salad or fruit except oranges and tangerines that could be peeled. It was before the banana age. Nor was there much heating. We sometimes had a stove or more often a brazier filled with glowing charcoal in the sitting room. It was stricter at the customs as a rule than it is now and every town had its octroi if we made an excursion. We did not know of the connection between malaria and mosquitoes but it was an English superstition that an attack might come from being out at sunset. We often arrived at a station in the middle of the night or set off at four in the morning. It was a life designed to shock the child care theorists to the core but oh, what an advantage it has been to me! I can vary my hours instantly to suit either side of the Atlantic, I do not mind where I sleep provided that the place is reasonably clean, the only thing that bothers me is a draft. Every nursery rule was broken during those years, I ate whatever my parents ate including gazelle and octopus, and never had a day’s illness until I caught a slight attack of German measles from a maid on one of our visits to England.

The only thing that I resent is that I did not know what Clio was offering me. It was the eighteenth century, at least at Naples. Scholars read about it, I have lived in it but alas, although I remember the flavor, I forget the details. Life was tougher and death always near. There was more individuality and color, much more eccentricity, perhaps because the weaklings perished. People believed in their opinions, sometimes they had a “cause” for which they were willing to die but it was simple stuff, the theoretical hair-splitting of today was unknown. (I should have caught a hint of it had it been in the air.) I do not think that human nature has changed very much since prehistoric times but each age has its atmosphere that cannot be transmitted through books and it ought to be an object lesson to the artist. He has to be in advance of his time yet he must also recognize that though the essential elements of his work may survive, the mood, the light and shade will never have the meaning for a future audience that they had when he created them.

Yes, if a century had lost itself and I had woken up in 1802 adaptation would not have been difficult. I knew that there were streets down which it was dangerous to walk after nightfall, Italians talked as casually about brigands and blood feuds as we spoke of Guy Fawkes Day and fireworks. The roads were turbulent, sometimes there were fights but nobody dreamed of sheltering me from the news as children are isolated nowadays. Outbreaks of plague and armed soldiers on the trains were as natural as the small, sweet oranges or the enchanting emerald lizards.

I accepted these hardships with pride. It was an honor, as my parents said, to accompany them abroad instead of being shut up in a nursery. I also knew that it mattered more if I were naughty on the Continent than at home because I discredited not only myself but every other English child. And now what do I remember of the cities with their enchanting names that were already so familiar from my mother’s stories?

A pole creaked, the rain beat steadily on the black hood, we could hear the waves slapping against the side of the cradle or what was the new word that they had used, gondola? I was wedged between the knees of my mother and father and we seemed to move, saying nothing, for hours. I tried everywhere to find a peephole but was told to sit still. It had been a long journey from England although we had broken it by spending a few days at Lugano. (I remember nothing of this visit to a place that was to be so important to me in later life except that it had rained there and I had been given my first paintbox.) Now I felt cramped and restless; I wanted my supper.

Suddenly there was a rush and a yell. I caught a glimpse of the Mediterranean night with its soft, almost bodily darkness. Then we shot into a harbor of wavy, brightly lit marble. A carved balustrade vanished into the sea but there was a roof overhead and people stood watching us from a gallery. A barelegged man leaned down from the flight of stairs, lifted me out and set me down beside a pile of red carpets stacked on the first-floor landing. The reflection from the lights, the tassels on the hood, bobbed up and down as they handed up the luggage. So this was Venice? The ground floor of the hotel was completely under the sea, it was a glorious adventure.

About every twenty-five years a particular combination of wind and tide floods the entire city up to the level of the first-story windows. The following morning we went round the Piazza of San Marco and up to the Cathedral by boat. “Remember this, Miggy,” my father said, “it may never happen again in your lifetime.” (It did in the late twenties and occasionally in recent times but then I was in England and merely saw the pictures, how familiar they were, in the illustrated papers.) There were few pigeons, they were clinging miserably to cornices. Only the names of the cafés were visible. Yet even at that age I was aware of an extraordinary beauty, of palaces rising from the Adriatic as if the architects had b

uilt them to be entered, not through doors but through porthole-shaped arches. Alas, that December the brightest marble lost its color and the wind blowing along the narrow canals gave us all coughs.

We went to High Mass at San Marco on Christmas Day and stood on planks with the other worshipers. My father lifted me up to see the Cardinal’s red robes (he became Pope shortly afterwards) but the incense suffocated me and much as this may surprise some people, the candles and the chanting seemed remote and cold after the friendly Noah’s Ark warmth of the little Protestant church to which I was taken at home. After the service the only way to leave was by boat.

Venice itself left me with a mixture of good and bad impressions. The Campanile was lovely, it was still the old one that fell down a short time afterwards. Fräulein led the way, I panted after her because it seemed a very long climb until we came out into the sunlight above a panorama of islands and water. It was one of my original landscapes, houses, bridges, and always somewhere a ship. It was much, much duller when as part of my lessons we had to go to picture galleries. I was too young for Titian or Carpaccio to arouse my imagination and I preferred feeding the pigeons. There were fewer of them in those days than there are now and it was quite a feat to lure them to the far end of the square. I learned some new words, however, like porphyry and lapis lazuli, and it was useful to know something about the Doges when I discovered Marco Polo, three years later.

Do I remember the Rialto or is the memory a reflection of later visits? I know that I trotted up and down cold, narrow streets in search of balls to hang upon the tree that had mysteriously arrived in our sitting room. I had never liked Christmas very much and the more Fräulein chattered about reindeer and the letters that Willie had written to Santa Claus, the more determined I became not to be tricked.

On Christmas Eve I pretended to be asleep. Several times a head peeped round the door. I kept my eyes shut, my ears alert. Finally somebody whispered, “She can’t still be awake.” I did not move, I tried not to breathe, finally the rustles ceased and a fat stocking was fastened to the foot of the bed. Enjoying the moment thoroughly I sat upright and said firmly, “I knew you were Santa Claus.”

I was not smacked (I deserved to be!) but I was told sternly that if I did not go to sleep at once, that very minute, the stocking would be taken away. Of course I was infuriating but why force make-believe upon a child when the facts of nature are so much more exciting? I was perfectly willing for grownups to revert to play provided that they did not try to deceive me. Let them tell me stories on the free and open basis that these were merely tales and I would listen to them happily but it was undignified to be asked to accept an old gentleman bustling down the chimney.

Another exploit was getting lost. I upset an inkpot during lessons and Fräulein, muttering, “The little devil, what can I do with such a child?” snatched her own sponge to mop it up. My mother took her into a chemist’s shop to replace it and left me outside with my father. It was a real apothecary’s booth. There were decanters of amber and violet liquids in the window, a glimpse of white porcelain jars and a smell of orris. I decided to follow my mother and investigate. It was dusk and neither of us had noticed that there were two doors. I pushed open the wrong one and found myself facing a barber. A lot of men with soapy faces looked up in surprise. The barber in his long white coat came over and asked me in Italian what I wanted. I shook my head, he repeated the question in English.

I was looking for my mother who was buying a sponge. Of course that was next door, come, he would take me there. To add to the confusion the shops were between two streets and by the time that we arrived, my mother had left by an opposite entrance. There was no sign now of parents anywhere. I was not to be frightened, the barber said, he had children too, my mother would come for me very soon and in the meantime I could watch him at work. I assured him indignantly that I was never, never frightened, I told him the name of the hotel where we were staying and added firmly that I could find the way back by myself. What a glorious opportunity it offered to explore Venice alone! I could hang over the parapets and study the canals without Fräulein tugging at me and saying, “You’ll get a sore throat lingering by that stagnant rubbish.” I might even get aboard a ship without anybody seeing me. The word “lost” has two meanings, one is to be alone but the other is to escape and it was the second that appealed to me. At that moment my family arrived, stupidly frightened. My father was being reproached for “not being able to mind the child a minute.” I was even more annoyed when the barber patted me on the head and called me a bambina, I knew that word, it meant “baby.”

My governess took to her bed. “A lady by birth” could not cope with such a little monster of wickedness. She remained there to my huge delight until we left for England two days later.

It was another winter and we were in Rome, this time without a governess. Did I know what an event this was, my family asked? Sometimes people spent a lifetime’s savings to come to the “eternal city” and here I was, only eight, with the treasures of the world open in front of me. “And now, darling, you have been poring over Baedeker for days, what would you like to see first?”

“The Colosseum,” I squealed, “because of the gladiators.”

There was a horrified silence. My father explained that everybody went at once to St. Peter’s. So off we drove in a bitterly cold December wind while I reflected sulkily upon the oddity of parents. I knew that I had to wait for anything that I wanted but was it fair to offer me a choice and then snatch it away? The columns and the marble made no impression on me. The towering statues in their rigid, stone robes seemed cold and unfriendly. I dragged behind with only one thought in my head, how soon would my parents tire of staring at all those chapels and take me back to the hotel?

How different it was the next morning! The wind had dropped, the sun was out and I tore into the arena, Baedeker in hand. “The lions,” I shouted, “look, the lions, they came up there!” Some silly tourist asked me if I wasn’t sorry for the Christians, I dived into lovely underground passages, I tried out seats all round the amphitheater, I even hid a chip of marble in my pocket when nobody was looking although I knew that this was a sin. Why wouldn’t people answer my questions? How old would I have to be before becoming a gladiator? Was a shield very heavy? Were the prongs of the trident pointed and was the net the same as the one used now to catch butterflies? “She knows more about it than the guide,” an old gentleman remarked. Yet at the time I had not even read Henty, there was only the one page in Baedeker but it was outdoors, I could run about, it belonged to my age.

Many years later I had a vivid dream. I felt that I was being given the chance to step back in time to see one episode from the past. I ought to have asked to listen to Sappho or to watch Hannibal leading his elephants over the Alps. I demanded instead a good seat at the Games and promptly, of course, woke up.

We stayed that December at a hotel in the center of Rome. I happened to return there a few years ago and the flowers, the gilt chairs and the sense of some discreet drama being acted out in a room along one of its innumerable corridors appeared to have survived half a century of change. All that I missed was a stolid figure on short legs, in the blue coat and narrow tippet of fur that had been the uniform of 1902, scribbling in rough, uneven letters “Rufus was a Roman boy, he was a gladiator,” along a much thumbed page in an exercise book. What is the relationship between a person of such infinite confidence, such wary hardness and myself? One is so much younger at sixty. This is surely one of the mysteries of Time that is almost interplanetary?

It was there in the restaurant under perhaps the same frescoes of the seasons that I was allowed to sit up for dinner for the first time. A long table nearby was set with silver and flowers and the headwaiter told us that some diplomats were expected. I watched them take their places with great interest, the men wore black instead of the mulberry-colored silk that I had seen in Titian’s banquets but the bare throats and arms of the women blazed with jewels. I g

lanced up gaily at their faces and froze in terror. It was as if I were looking at malice and greed as they might have appeared in some medieval morality before an unworldly audience. I felt in a flash what would happen to me if I fell into their power, if I were one of those barelegged urchins, for example, who hoping for a few soldi ran after the carriages to open the door, or some old woman in her hovel who was behind with the rent. “Something has shocked the child,” my mother said, was it that the ladies had no sleeves, that was called evening dress. It would not have mattered to me if they had worn no clothes at all. “They are not alive,” I stammered because I had no vocabulary to explain what I felt. Perhaps it was an illusion and I maligned my neighbors but I have seldom had so overmastering a sense of evil in my life.

I watched women washing clothes in the yellow Tiber water and picked up chestnut husks at Frascati. I stood enthralled in front of a sculptor at the Villa Borghese, he was copying a statue in a dark clay that I mistook for bronze. At Pisa, I remember only the Leaning Tower and an icy wind. I had never heard of Robert Browning but I recognized our Florence in his poems a few years afterwards. The streets could not have changed since the eighteen sixties, they were full of stalls and carts, sometimes even of goats. There were plenty of old ladies lodging in bitterly cold pensions or lofty palazzo rooms, to escape, as they thought, from an English winter. Some painted water colors, others read guidebooks. They marched in black buttoned boots from church to church, admiring canvases that are now unfashionable, uneasily conscious that the painters (like Filippo Lippi) had not always led virtuous lives but assuring each other that “it’s a man’s art that matters, dear, not his life” whilst staring at a panel of some kneeling patriarch half obliterated under smoky varnish in a corner of the ceiling. They shouted violently at peasants who struck their mules (I have read since that a concern for the welfare of animals was the only political outlet then permitted to a lady), they founded tearooms. For all their good will, I doubt if they understood Italy yet perhaps we should not laugh at them, stumping along with their twin torches of Italian beauty and English stolidity. Comprehension is not always necessary nor, in general, should a foreigner try to reform another country, yet sometimes the stranger in his “very serviceable suit of black” perceives the essence of a past that has become merely a hindrance to the native.

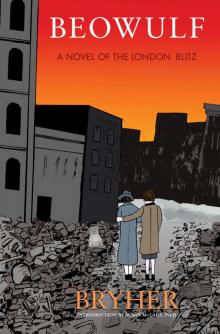

Beowulf

Beowulf The Heart to Artemis

The Heart to Artemis