The Heart to Artemis Read online

Page 7

We stared at Florence from the outside just as Mrs. Browning had watched it from her windows. “Look!” I tugged at the sleeve of my father’s overcoat, there was a shepherd boy hardly older than myself, crossing the bridge with a kid over his shoulders. The squares were wide, the streets were narrow, they were almost as dangerous as the cars are today, with coachmen yelling, flourishing their whips and each trying to pass a rival’s carriage. We flattened ourselves against the wall to get away from the donkeys and their fleas, we jumped back as the wheels of two barrows touched and the owners screamed like brigands at each other among the spilled lemons.

I almost made the headlines of the newspapers, however, trying to burn down the Uffizi. In 1903 there had been little change since Elizabethan times in the attitude towards children. I suppose that we must have inherited the former status of slaves, we were sometimes petted and often smacked; absolute obedience was the ideal though it was seldom achieved in practice and while we were forbidden to have opinions of our own we were expected to share adult interests beyond an eight-year-old’s understanding. It was a Spartan discipline. Every morning I was taken to visit churches, galleries or museums. All paintings looked alike to me with fat cherubs, masses of cloud or old men praying in dingy, umber robes. I particularly disliked Michelangelo. His name was repeated so often that I sometimes wondered if it were another term for Italy. To look at pictures might be for “my future good,” a phrase enough to wreck any self-respecting child’s day, but what I wanted was to run along the Arno and to watch the puppies chasing their tails in the sunlight. It was dull, it was cold, I shut my eyes in desperation, screamed, “I won’t look, I won’t look,” and walked backwards into a pan of charcoal, the accepted method in those days of heating both hovels and palaces.

Embers flew all over the wooden floor, the custodian, cursing and half asleep, grabbed the brazier just as it was toppling over, several copyists sprang from their easels to stamp out sparks. People scolded me in half a dozen languages, they glared at my mother and insinuated that a bambina should be left outside with a nurse. “We thought we could trust you,” my parents said reproachfully as they hurried me into another room. For once the reproof had no sting. “I won’t look,” I yelped, “I won’t look however much you scold me. I hate museums.” Finally we compromised; if I would walk round with open eyes, holding my father’s hand, they would give me the book that I wanted so badly that very afternoon.

I had seen a horror comic with the most wonderful cover in a shop window of the Via Tornabuoni. A man was lying on the ground with a spear through his chest while two warriors stood above him, slashing at each other with swords. According to an inscription underneath it was “the fight for the body of Patroclus.” Who was Patroclus? Why had he been killed? Authority objected of course; “You won’t really like it, you know” but a bargain was a bargain and I insisted. Oh, what hours of toil over horrible Greek verbs I might have spared myself later had I allowed myself to be overruled. The book was The Boy’s Iliad by Walter Copeland Perry and it led me back to museums and not away from them.

I began the Iliad in the train and now I can never see the Tuscan hills without thinking of the boyhood of Achilles. Chiron fed him on the hearts of lions. My mother, consulted, thought that these might be tough. I wished that I could have watched the foot race or followed Penthesilea (Perry had wisely included all the myths), I tried to imagine the outline of the camp on the shore, going back in my head and beginning again, if I felt that I had not got the details right. If I had been able to draw the scenes that I imagined, Troy would have been startlingly Elizabethan with Gozzoli touches. The walls were the sun-baked blocks of the hill towns that we passed, a sentinel’s cloak was not army scarlet but the red of the anemones in the grass. My white canvas tents were wrong but I did not know of any others. What was a tripod and why was it so valuable as a prize? Were greaves anything like gaiters and were they fixed on with straps? How was a javelin thrown? What I needed was Lorimer’s Homer and the Monuments but that book, alas, was not yet written. I heard the chariots turning on the sand as I dreamed, the sea wash thundered in my ears and my sleep was full of the beauty of the ships.

It is strange that after The Swiss Family Robinson the most profound impressions of my childhood came from Shakespeare and Homer. I still think Perry’s retelling of the stories for the young is unsurpassed and I am particularly grateful that he used the Greek names for the gods. These gave me the clue to the objects that surrounded me. I lived through and with the myths as I suppose a later generation identified itself with what it saw in films. Besides, the appeal was direct and simple. The choice of Achilles was my own. Who wanted more than a brief life provided it were crammed with adventure? An hour of action was worth a lifetime of security.

I soon got The Boy’s Odyssey but this was disappointing. The cruelty to Polyphemus shocked me, it was, after all, his cave and the slaughter of the suitors upset my nursery ethics. Exactly what had they done? Even now the dark and savage side of the ancient world seems to emerge more clearly in the wanderings than in the fight before Troy; in this, the poems are true to life because the years following a war are often more brutal than the calamity itself.

My friends tell me that Perry’s versions are not simple enough for the modern child. To me, the theory that a limited vocabulary should be offered to an age group is more horrifying than any atomic threat. We have neither the right to stunt development nor to make it too easy; the overcoming of obstacles is one of the greatest joys in life.

Achilles had a rival, however, in the Perseus of Kingsley’s Heroes. I think the flying in the story brought my fantasy wings although I did not know then that I was to love the air so much. Years afterwards, following analysis, the Gorgon became for me the symbol of truth. We can endure this only if it is reflected in a mirror or shield, if we have to face it directly we die. It is also part of another story, the eternal struggle of Mithras. The best and most daring among us cannot hope to catch more than a second’s reflection, and that at long intervals, of absolute verity.

If Florence was the Brownings, Naples was the eighteenth century, as I have said, and I loved it more than the rest of Italy. The streets were a child’s playground, they were noisy, dirty but how they blazed with color! The donkeys drew their carts down alleys so narrow that the wheels almost touched the walls. We brushed past vegetables arranged in pyramids, there were onions, leeks like green ribbons on a white dress and gay rosettes of radishes between balls of artichokes and hoops of lemons. A trader wailed mournfully, windows opened and bargaining began while baskets appeared and were let down on ropes from the top stories. Oh, what arguments there were! Sometimes a basket hurtled down a second time with a rejected bunch of carrots. People left their pans of fish or macaroni to join the fray, almost all the cooking was done in the open air, the donkey snatched a carrot top, coins jingled. I stood on tiptoe on the front seat of our carriage because now the crowd was blocking the road and we could not get through it. “Oh look!” I turned excitedly, I had seen the woman with the black hair falling untidily over her face and the big, open mouth before, “Isn’t she just like the Gorgon on the mosaics?” She was going to throw something, yes, we dodged, and a lemon missed the dealer’s hat by centimeters. Everybody yelled, the coachman cracked his whip, my father consulted his watch, what did they care for the time-consciousness of the north? The cart moved on a yard to repeat the same drama next door. Our driver turned somehow and drove to the lower road down a real flight of steps. They were broad, it is true, and there were only about a dozen of them.

Little girls looked up, waved as we passed and then went back to their proper occupation, catching lice in each other’s hair. Children of my own age were at work (I still think that most of them were happier than if they had been at school) and, although they went barefoot and were thin, seemed gay. They often danced, not for tourists but because somebody had given them an orange. It was the same world that the Latin authors have described exc

ept that the gutters might have been cleaner and the cobbles kept in better repair under the emperors.

It was that day that we climbed Vesuvius, slipping two feet back in hot lava dust for every foot that we advanced. I held my father’s hand and we looked at the crater, I half hoped that a sudden eruption would drive us down the slope as in The Last Days of Pompeii, a not very satisfactory book that I had just read in the ever useful Tauchnitz. I preferred Whyte-Melville’s The Gladiators. Still, it was easy to imagine being trapped in the oozing lava as if it were a bog. We looked round for my mother but she was nowhere to be seen; there was only an angry crowd in the distance. She had been following some way behind us when a number of men had thrust her into a carrying chair, despite her vigorous protests. Halfway to the summit they had set her down to demand their pay. My mother had grasped her sunshade firmly and had told them that she had no money. They would have to wait until they reached my father. Vesuvius had a bad reputation as to brigands although officially it was supposed to have been cleaned up. Apart from two other tourists we were alone and we were all a little uneasy. To be taken prisoner when people were flourishing their fists and shouting was not quite the same as reading an adventure book. My father refused to pay one lira till we had got back to the station and going down, in tremendous, scooping strides, was quicker than our ascent. It turned out all right in the end but judging from the noisy atmosphere around Pompeii today, the neighborhood has not changed much during the intervening years.

I reached Pompeii at last, the wine jars and the loaves were exactly as my mother had described them to me but on that special day, perhaps I had expected too much, I was deserted by Clio. I ran along the chariot ruts, the past was at my elbow but a blue sky, an insect buzzing around a pillar, held me firmly inside the present. What did “the mysteries” mean, I begged, not knowing that they were the fruit of much experience, only to be discovered alone. I touched the stones, I knew that it needed but a single incident or word and I should enter into antiquity instead of looking at the ruins but nothing happened. We can imagine another age but we cannot leave our own however much we try to transpose ourselves. The centuries pass, a little color remains but the true hopes and fears of our ancestors will always be just off focus in the way that we can remember childhood but can never re-experience its emotions.

Baia consoled me with its blue sea, short turf and the enameled lizards that I already associated with Apollo. It was a holiday place, we ate an omelette and fresh oranges at some primitive inn and I played on the slopes outside it afterwards among stones from old Roman villas. There was a cruel custom of sending dogs into the neighboring caves from which they staggered out, poisoned by the bad air. Most English tourists paid the men not to drive the animals inside but this, as we realized, only helped to prolong the custom. At another place, a small, half-naked boy ran down a passage with a raw egg in his hand to emerge with it apparently cooked. Actually, as my father explained to me, he changed his first egg for a boiled one at some corner. His trip was merely through a tunnel heated by hot air and was pleasant on a winter day because I pushed in myself as far as I was allowed.

Which was the cave that I visited alone with a guide? It was not at Baia itself but in that neighborhood. I went down long corridors towards the “underworld,” a dark sheet of water, and emerged triumphantly but, to my mother’s dismay, with black smears over my hat and coat. I think the pathway had been lit by torches.

We were in Naples once for New Year when all families able to afford them bought eels. I shall never forget our drive across the fish market. Urchins sprang onto the steps of our victoria, they thrust a snarling head and a slimy wriggling body almost onto my mother’s lap. It was useless trying to leave, we were wedged into a solid mass of carriages, vendors and stalls. A beggar’s rags were held together by a patch of scarlet, there was a dark clip of coral on a woman’s shawl. We could not hear ourselves speak, the yells, the whip cracks and the ringing hooves were louder than thunder. Men who looked Turkish rather than Italian held up pails of mussels, two men bargained clamorously over a shallow dish of oysters. There were skates and cuttlefish, spines stuck together with mud and glazed oblongs that we could not recognize. The ground was slippery with oily skins, fish bones and scrunched shells. It stank, it was a madman’s picture of hell, I was frightened that our horse would fall and excited at the same moment, while beyond the quays sailing ships from the beginning of time were anchored next to modern liners waiting to take emigrants to the States.

It was always a world of fish, as we can see from the surviving paintings, and I haunted the Aquarium. Again each window was a mosaic, only it was fluid and vertical, instead of being part of a pavement. Some of the fins had dots like grape pips, I recognized a mullet hiding in the corner, what was the name of that creature with long, lemon stripes across its back? My favorite place was in front of the sea horses, surely they had just been broken off a pediment? The rose and orange tassels of the sea anemones opened and shut, a coral full of miniature caves that was not at all like the necklaces that the traders dangled on their trays seemed to be the playground of a shoal of sprats and could that porous, sticky lump possibly be a nursery sponge? To tease my mother and test my own courage, I forced myself to watch an octopus edge sideways across the sand until the dark tentacles whipped suddenly about a rock. What would happen if the glass should break? It was enthralling but it was puzzling as well. How long was it possible to breathe under water? Could a fish think? After we came out into the sunlight we bought newspapers from a boy my own size who told us that he went to English classes at night school and wanted to go to London. I have always wondered whether he got his wish.

Yet Death walked openly through those crowded Neapolitan streets. A bell tolled or rather it was rung by hand, people began to scatter, we, ourselves, were swept inside a shop. The sound came nearer, a man started to pray, my mother ordered me sternly to hold my breath. Four men walked along the deserted street, carrying a bier. Their dirty white overalls almost touched the ground, their faces were hidden by their hoods, I had looked at so many pictures of such scenes in the galleries that I muttered “plague” and nodded with the rest. No, I was not frightened, it was not measles, it was just the pest. I had read about it in my history book. Really they must not be afraid.

I did not feel so confident when a beggar grabbed my arm as we were entering a church, a few days afterwards. He was kneeling on the ground, his deformed and noseless face was at the level of my eyes and supposing him from the Bible stories to be a leper, I jerked my shoulder away from him and howled.

We sometimes went to Capri for the day. I am glad that its landscape was a part of childhood but the place belongs to a later date in my story when I was there with Norman Douglas. All the same, I never walk up the hill through the aromatic rosemary bushes towards the villa of Tiberius without my father’s lectures upon the superiority of the law courts in England to imperial despotism echoing through my mind. Naturally the English were more moral but it would be pleasant to have one’s wishes immediately fulfilled without a judge or elder saying, “But you will be sorry afterwards,” in a hurt, astonished voice.

I disliked the Blue Grotto intensely; a heavy fisherman sat down on me as we entered it and then, as now, Capri was full of guides. One man followed us onto the steamer protesting that he had lived in London and was almost an Englishman, had he not learned to drink tea in the English manner, half full of rum? It seemed cruel to tell him that we had never heard of this curious custom ourselves. “You must not laugh, Miggy,” my father explained afterwards, “there is great poverty here and he wanted a job.”

Why was Italy poor? It had the sun. Yes, my father agreed but there was much mismanagement and some of the officials were corrupt. I listened to his explanations with excitement, they were like the stories of the emperors, and it was an invaluable training, no matter how mixed up I got at the beginning, for my subsequent life.

My father also invented a game to pass th

e time when I had read and reread all our books, including his own, I was to imagine that I had to take a party of tourists round Italy. Learning depends upon interest. Sums were a nightmare to me but I had no trouble in working out the cost of tickets and sleepers, first or second class, in liras or pounds, I looked up trains and steamers, planned how I could show my group the most things in the least time. I do not know if some intimation of the air age was already stirring in my bones but I am one of those universally despised people who depend upon a first, sharp impression, I can really get more out of a hurried tour than by staying a leisurely month in a single city.

The greatest of our Italian expeditions was Paestum. Hardly any visitors risked such an expedition in 1903. Only the main temples had been uncovered, the swamps had not been drained and it was so full of malaria that it was only safe to be there during the middle of the day. There was no museum and no hotel but it was full instead of delicious rumors about brigands and, according to Baedeker, of a special breed of ancient, white oxen.

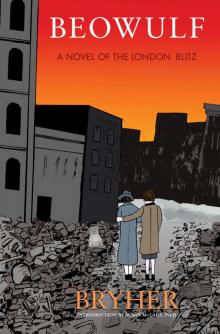

Beowulf

Beowulf The Heart to Artemis

The Heart to Artemis